Should we try first to dispel the fog as curators love so much to do? The Black Square is a painting by the Russian painter Kazimir Malevich. He painted the first of several versions in 1915. A black square, however, appeared earlier in Malevich's stage design for Victory over the Sun by Aleksei Kruchonykh, Mikhail Matyushin, and Velimir Khlebnikov. The opera tells the story of a group that attempts to destroy reason by disrupting time and capturing the sun. Malevich saw this work as the first painting of Suprematism – his coinage for a style that abandoned representation in favor of shapes and colors. Although in 2015 researchers from Russia’s State Tretyakov Gallery found a handwritten inscription underneath the painting saying what they believed to be: “Battle of negroes in a dark cave.”

The story of this exhibition’s adventure with art begins as we capture the sun and destroy reason. Are we looking for something that can only be unlearned in the absence of light?

What is painted here?

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say.

Horodi created this work as part of her job at “Net.Haver” (net.friend), a social internet platform for adults with “intellectual disabilities”. It is part of a series of videos mediating canonical artworks. Horodi speaks about this work :“The world of people with intellectual disabilities is artificially limited by their environment, often out of a belief that they should be protected from certain thoughts… In working with people with intellectual disabilities and talking to them about the same issues that they were prevented from discussing elsewhere, we get to fight alienation with them, theirs, and ours.” (-Shai Lee Horodi translated from Dvarim Baolam podcast, as all her other quotes in this section)

But Horodi’s Mediating Videos circulate beyond Net.Haver. Alienation is in every corner. Listening to Horodi’s voice-over I notice an invitation to linger in the shade with Malevich and her. Perhaps an invitation I can only follow when I trick myself or am tricked by the artist to believe I am not this work’s target. I jump beyond symptoms and join Malevich’s fight against reason to find empathy for our lack of understanding. But is art mediation the gateway to allowing everyone to enter the convoluted realms of contemporary art, or what distances them with the lesson that they can only experience art through the mediator’s words? And who is them? The French philosopher Jacques Rancière taught me that “to explain something to someone is, first of all, to show him he cannot understand it by himself.” (-Jacques Rancière, in The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation )

Horodi herself is not surprised by art that is engaged in the segregation of people. After all, in her words,“It is impossible to produce art that will not express social relations. And if the social relations are indeed relations of exploitation as they are in our society, then that is what artists will express.” I can identify in this work a crack between explanation and exploitation It brings the pain of distinction and the frustration of not understanding into light.“It enhances a painful moment where a viewer sees something taken from him.” Or her.

Get hit or drop something and break it

Horodi: "When I want to take a break without interrupting my concentration, I do juggling. If you are ambitious, try learning to juggle three balls. If less, then you can practice throwing a ball behind your back with your right hand and grabbing from the front with your left and vice versa until you do it steadily, without too much effort".

That's how you can make balls.

I only made two balloons, yet I managed to keep dropping them on the floor. The juggling balls are a recurring motif in Horodi’s practice. In 2020 she created the work Three Balls in Two in which her hands do the actions required to do three-ball juggling, but the third ball is missing. “Juggling is done when there are too many balls,” Horodi tells the artist Yonatan Zofy. “I thought of it in the context of The 20th Seminar by Lacan. It talks about the indulgence of man and woman as fundamentally different. For the man, it is a pleasure of the phallus; he can point to pleasure and find it in everything. And the woman says, ‘it is not everything,’ and that is her pleasure, to say that it is not everything, ‘you did not point for everything,’ ‘you could not catch all pleasure. Juggling is the answer to the woman who said it. It’s the masculine thought of a solution, the omnipotence of potency. There are two balls, and then the woman says ‘no, that's not all,’ then the man says ‘oh! Is there another ball? No problem! 'And the juggling movement begins. But it is clear that what the woman means is not that there is another ball; there is something else that cannot be named.”

--Shai Lee Horodi translated from Marbe Einaim

I have heard that Moshe Halbertal, a professor of Jewish thought said that a good Talmudic Sugia (issue) is one that succeeds in holding as many balls in the air as possible. The dispute culture of the Talmud, one of the central texts of Rabbinic Judaism inspired the layout of this exhibition. The original polysemic text (here the artwork) is placed in the center, surrounded by different literature responding and interpreting it from various languages, traditions, and perspectives.

Juggling between points of view, there is always something that refuses to be written.

Get hit or drop something and break it

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say.

_gif.gif)

HOW

TO BE

WITH

ART ?

Curator: Maya Bamberger

SHAI LEE HORODI

Retractive

The title of the artist’s book breaks the word “understanding” into its two compounds: under + standing. The word under is equivalent in old English to among or between. So, to understand something is to stand among it. In order to stand between Aviv’s words, one doesn’t have to cohere them, as usually happens with those standing outside the work – either curator who explains it or a viewer that fails to understand.

Retractive

What is painted here?

The ordinary response

The response to atrocities

The response to is to banish them from consciousness. Violations of art too terrible to utter aloud. The meaning word unspeakable. , refuse

Denial does not work ghosts refuse their graves. Stories are told. Remembering truth restoration of social order healing

Individual victims

Trauma.

Emotional contradictory, and fragmented undermines credibility

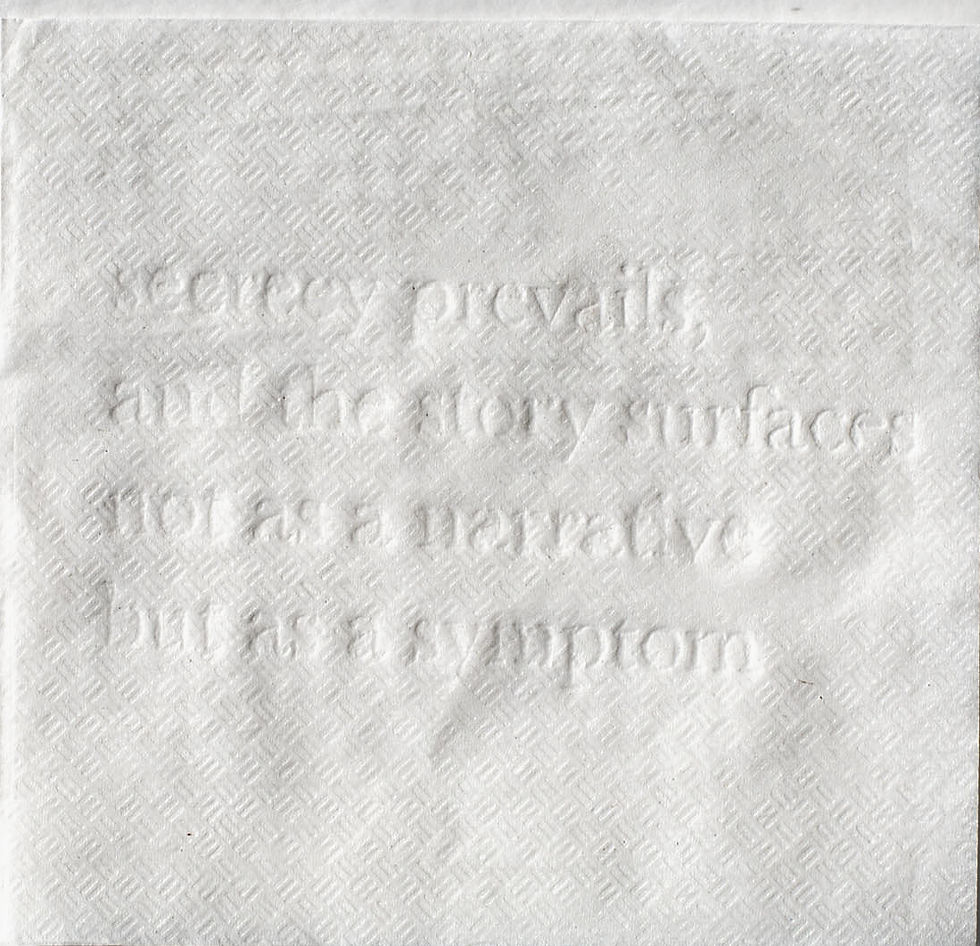

The story of the traumatic event surfaces not as a verbal narrative but as a symptom.

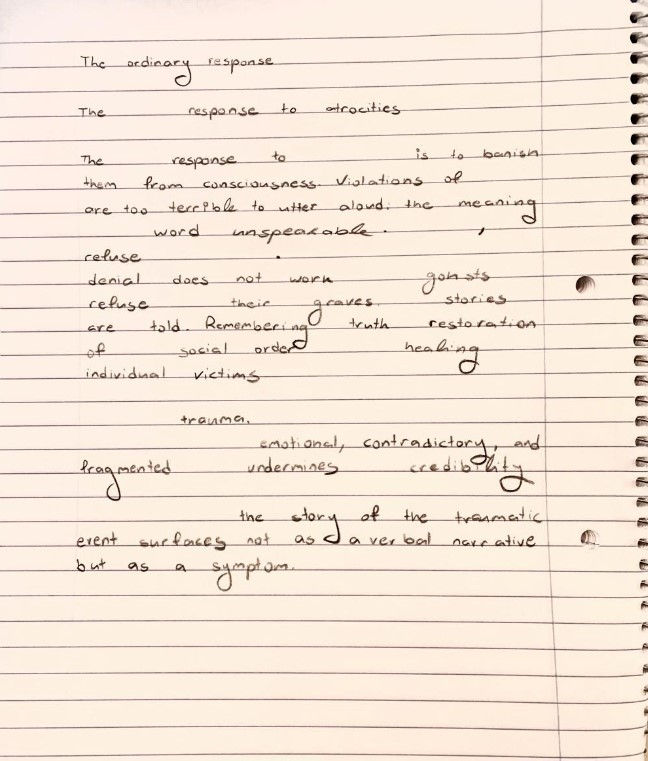

I imitate the perforated way Roni Aviv traces the opening lines of ״Trauma and Recovery” by Judith Lewis Herman, but choose to omit other words. Each hole in the text can be filled to tell a different story. How can a text about her work speak the banished unspeakable knowledge that surfaces as a symptom? How can the viewer internalize disintegrated knowledge? Lewis Herman writes that witnesses are also subject to the same forces of trauma. It isn’t easy to bring the pieces together and put them in (linear) words.

Contained

Aviv: Choose a corner or an object in the house and photograph it at least 10 times. Examine what you are able to extract from this object through observation. Experience different angles, different times of the day, different lighting, close-up versus an entire scene.

As part of the selection of pieces of text that Aviv incorporates into her book by tracing over a light table, she also copies parts of the Wikipedia entry for “floor”: “Floors may be stone, wood, bamboo, metal or any other material that can support the expected load.”

Responding to her prompt, I have taken ten pictures of my floor at home. Positioning my body in relation to a floor that can support the expected load, I took the first step toward her work. Towards supporting the unspeakable. Towards recovery. Towards being with it/her.

“A photograph shows something in relation to its position or lack of position in a world I find myself on the floor for many occasions I slide around looking for all the things I've misplace hoping the floor will reveal them. It usually doesn't.” (-Roni Aviv)

Contained

Spaced

“The closer you get,” she writes, “the clearer you see, until the switching point where it becomes harder and harder, until all that you see is blurry fuzzy outlines.” The closer I get to her work, I only see those blurry fuzzy outlines.

I try to illuminate the meaning behind Aviv’s work. I read the surfaces of Aviv’s photographs and turn them into lines that can be read consecutively.

What's under the photo? Under the written word? Is it what ignited it all? Does it have a source? At what timeframe does it occur? And occur? And occur? Is it possible to distinguish between the time when the trauma occurred, the time when the work was created, the time of writing this text, and the time it is displayed in the exhibition? The trauma leaks through the holes between the words, behind the order of the language, it leaks leaks leaks from Aviv’s body into the paper. Sometimes she uses her body weight to emboss the words deep into the paper. Sometimes she leaves behind only the punctuation marks.

“The linear responsibility weighs me down.” Aviv writes.

So, Write in

fragmentation, in a

plurality of voices, write

like women before you have written.

Write like Roni Aviv.

Write down what your head cannot

understand, but your hands are already writing.

Write the perspective of the object, of the floor, of the artist, of those who are looking for

words and couldn’t find any. Write to host the

trauma. Write when the words themselves

d i v e r g e. Write what still has no language.

Write when the encounter with an artwork

brings with it words for what you had no words before.

Looped

While relating to the practice of using sourced written material, Roni Aviv differentiates between five ways of “finding or pouring” meaning: additive, looped, retractive, spaced, and contained. I offer these five words as titles for five paths of “finding or pouring” meaning in relation to her artist book Under Standing:

Retractive

Introduction

While searching for an entry point to the work Scream by Vanessa Sandoval, I came across an essay she had written titled “Astronauts in the Jungle.” By theoretically placing astronauts in the jungle and shamans in the cosmos, Vanessa Sandoval calls us to encounter otherness through transformative actions rather than observe it from the outside. I suggest encountering the otherness in her artwork scream, through some of the points of view she offers:

I don’t know what this woman wants or how can I help her to speak up. I Open my mouth to digest the work. I open my lips wide for five minutes and 33 seconds, and the air molecules flow out of my mouth and condense on the screen. Does she want to remain silent? After all, words will chain her body and work into the cage of my or your interpretation nurtured by patriarchic and other orders. But Hélène Cixous once wrote that “by writing, from and toward women… women will confirm women in a place other than that which is reserved in and by the symbolic, that is, in a place other than silence. Women should break out of the snare of silence.” (- Hélène Cixous in “The Laugh of the Medusa”)

Wouldn’t she remain voiceless even if I wrote all around her? I am desperate to talk with her. Maybe instead of putting words in her mouth, I can just gently describe even the slightest of her vibrations?

A black rectangle and within it a woman looking down. Then, she looks up at me –at the camera - and begins opening her mouth. She blinks a lot and her lips tremble - she is obviously straining. The title of the work implies that she is screaming at me, but her voice is inaudible. Playing with the volume buttons also doesn’t do much. I am with her. “Every woman has known the torment of getting up to speak. Her heart racing, at times entirely lost for words, ground and language slipping away-that's how daring a feat, how great a transgression it is for a woman to speak-even just open her mouth-in public.” (-Cixous)

The Alien

Shamans in the Cosmos

In the essay “Astronauts in the Jungle” Sandoval writes that by wearing animals’ skin, Shamans become animals themselves and “access a change of position, occupy another point of reference, expand, find otherness and thus understand that our projected gaze is also part of the landscape—that there is another who watches us.”

Wear her skin, change positions, get into her mouth absorb in the visual syntax! Adopt the artist’s discourse and invade her language! But alas! Isn’t it the definition of perversion, born as a survival mechanism when a “mother tongue” to speak could not develop?

In ancestral communities in the Amazonian, everything has a consciousness. Therefore, when eating plants in ayahuasca rituals or eating humans, this other consciousness is digested and alters our point of view. But Astronauts are colonizers of space, Sandoval reminds me. I think that curators are rational colonizers of the visual jungle or visual outer space. I don’t want to do that! Sandoval suggests that the overview effect that astronauts experience when they look at earth from space can be seen as the intersection of an extreme outside perspective with the sublime understanding that their gaze is inseparable from the earth they see.

*

Amelia Jones taught me in “Body Art/Performing the Subject,” that bodies could reject predetermined values and meanings more effectively than silent objects. Bodies absorb what is happening around them, disrupt the relationships between observed and spectators, and encourage performative interpretive acts. In this project, aiming to reduce the distance from the artist I only met virtually, I developed an embodied curatorial practice: I asked each artist to give me a task from their daily studio routine that I could inhabit myself. These are also offered as a first key or animal skin for you to wear.

Sandoval: Open your mouth without closing it or swallowing until you feel that your body can no longer bear the imposition.

Shamans in the Cosmos

The Suit

The opened-mouth woman is not the artist herself. Sandoval herself only opens her mouth in her art while wearing a beard.

In a series of videos-performances Sandoval realizes these days, she invites scholars to discuss the notions of communication, interpretation, and language when they intersect with the dominant scientific paradigm. The artist performs in these interviews wearing a historical symbol of male wisdom, which gave the series its title: “The Jungle of the Bearded Lady.” What does this masculine alter-ego of the bearded lady allow her to say? How would I write wearing a beard? How would you read bearded?

The Suit

Quantified%20Self%2C%20digital%20print%2C%20100x150%20cm%2C%202021_tiff.png)

The open-mouthed woman is not the artist herself. Sandoval only opens her own mouth in her art while wearing a beard.

In a series of recent video-performances created by Sandoval, she invites scholars to discuss the practice of communication, interpretation, and language under the scientific paradigm that dominates the academic and cultural worlds. In these interviews, the artist performs while wearing a beard, a historical symbol of male wisdom, giving the series its title: “The Jungle of the Bearded Lady.” What does this masculine alter-ego, a bearded lady, allow Sandoval to say that she otherwise would not be able to say? How would I write with a beard? How would you read with a beard?

The Suit

A woman looking down from within a black rectangle. Then, she looks up at me—at the camera—and begins to open her mouth. She blinks a lot and her lips tremble - she is obviously straining. The title of the work implies that she is screaming at me, but her voice is not audible. Playing with the volume buttons also doesn’t do much. I am with her. “Every woman has known the torment of getting up to speak. Her heart racing, at times entirely lost for words, ground and language slipping away-that's how daring a feat, how great a transgression it is for a woman to speak-even just open her mouth-in public.” (-Cixous)

I don’t know what this woman wants or how I can help her to speak up. I open my mouth to digest the work. I open my lips wide for five minutes and 33 seconds, and the air molecules flow out of my mouth and condense on the screen. Does she want to remain silent? After all, words will chain her body and work into the cage of my or your interpretation, nurtured by patriarchal and other orders. But Hélène Cixous once wrote that “by writing, from and toward women… women will confirm women in a place other than that which is reserved in and by the symbolic, that is, in a place other than silence. Women should break out of the snare of silence.” ( -Hélène Cixous in “The Laugh of the Medusa”)

Wouldn’t she remain voiceless even if I wrote all around her? I am desperate to talk to her.

The Alien

Sandoval:

Open your mouth without closing it or swallowing until you feel that your body can no longer bear the imposition.

Vanessa Sandoval, The Scream, 2016, video, 7:22 min (performed by Nataly Vargas)

In her essay, “Astronauts in the Jungle,” Sandoval writes that by wearing animal skin, Shamans become animals themselves and “access a change of position, occupy another point of reference, expand, find otherness and thus understand that our projected gaze is also part of the landscape—that there is another who watches us.”

Wear her skin, change positions, get into her mouth, absorb the visual syntax! Adopt the artist’s discourse and language! But alas! Isn’t that the definition of perversion?

In indigenous communities in the Amazon, every thing on earth has a consciousness. Therefore, they believe that when eating plants, animals, or humans during spiritual ceremonies, another form of consciousness is digested that subsequently alters our own point of view. When astronauts move away from the earth towards the stars, they also experience a change of perspective, a term which is known as the overview effect. Sandoval suggests that the overview effect that astronauts experience when they look at earth from space is the intersection of an extreme outside perspective with the sublime understanding that their gaze is inseparable from the earth they see.

Astronauts are colonizers of space, Sandoval reminds me. I think that curators are rational colonizers of the visual jungle or visual outer space. I refuse to do that! Can perspectives change while maintaining sensitivities to otherness, without a full takeover?

Shamans in the Cosmos

Amelia Jones taught me in “Body Art/Performing the Subject,” that bodies can reject predetermined values and meanings more effectively than silent objects. Bodies absorb what is happening around them, disrupt the relationships between spectators and the observed, and encourage performative and interpretive actions. In this project, aiming to reduce the distance between the artist and curator (with the added challenge that we only met virtually), I developed an embodied curatorial practice: I asked each artist to provide me with a prompt or task from their daily studio routine that I could practice and inhabit myself. These can be understood as a first key or animal skin to wear.

Dioramas

While searching for an entry point to the work, Scream, by Vanessa Sandoval, I came across an essay she had written, titled “Astronauts in the Jungle.” Theoretically placing astronauts in the jungle and shamans in the cosmos, Vanessa Sandoval calls on us to interact with otherness through transformative actions rather than observing it from the outside. Here I suggest engaging with the otherness in her artwork Scream through the points of view that she herself offers:

_gif.gif)

_gif.gif)

I imitate the perforated way Roni Aviv traces a selection of words from the opening lines of Trauma and Recovery, a book by Judith Lewis Herman, but I choose to omit different words. Each gap in the text can be filled to tell a different story. How can I write a text about Aviv’s work that speaks to the banished unspeakable knowledge that surfaces as a symptom? How can the viewer internalize disintegrated knowledge? Lewis Herman writes that witnesses are also subject to the same forces of trauma. It isn’t easy to bring pieces together and put them into (linear) words.

The ordinary response

The response to atrocities

The response to is to banish them from consciousness. Violations of art too terrible to utter aloud. The meaning word unspeakable. , refuse

Denial does not work ghosts refuse their graves. Stories are told. Remembering truth restoration of social order healing

Individual victims

Trauma.

Emotional contradictory, and fragmented undermines credibility

The story of the traumatic event surfaces not as a verbal narrative but as a symptom.

Spaced

Additive

The title of the artist book breaks the word “understanding” into its two compounds: under + standing. In old English, the word under is equivalent to among or between. So, to understand something is to stand among it. In order to stand between Aviv’s words, one doesn’t have to cohere them, as usually happens with those standing outside the work—either a curator who explains it or a viewer’s understanding.

Retractive

Aviv: Choose a corner or an object in the house and photograph it at least 10 times. Examine what you are able to extract from this object through observation. Experience different angles, different times of the day, different lighting, close-up versus an entire scene.

“The closer you get,” she writes, “the clearer you see, until the switching point where it becomes harder and harder, until all that you see is blurry fuzzy outlines.” The closer I get to her work, I only see those blurry fuzzy outlines.

I try to illuminate the meaning behind Aviv’s work. I read the surfaces of Aviv’s photographs and turn them into lines that can be read consecutively.

What's under the photo? Under the written word? Is it what ignited it all? Does it have a source? At what timeframe does it occur? And occur? And occur? Is it possible to distinguish between the time when the trauma occurred, the time when the work was created, the time of writing this text, and the time it is displayed in the exhibition? The trauma leaks through the holes between the words, behind the order of the language, it leaks leaks leaks from Aviv’s body into the paper. Sometimes she uses her body weight to emboss the words deep into the paper. Sometimes she leaves behind only the punctuation marks.

“The linear responsibility weighs me down.” Aviv writes.

So, Write in

fragmentation, in a

plurality of voices, write

like women before you have written.

Write like Roni Aviv.

Write down what your head cannot

understand, but your hands are already writing.

Write the perspective of the object, of the floor, of the artist, of those who are looking for

words and couldn’t find any. Write to host the

trauma. Write when the words themselves

d i v e r g e. Write what still has no language.

Write when the encounter with an artwork

brings with it words for what you had no words before.

Looped

Roni Aviv, under standing, 2021

In relation to the practice of using sourced written material, artist Roni Aviv differentiates between five ways of “finding or pouring” meaning: additive, looped, retractive, spaced, and contained. I offer these five words as titles for five paths of “finding or pouring” meaning in relation to her artist book, Under Standing:

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

A selection of texts are incorporated into Aviv's artist book, which she does by tracing over a light table. One of the texts that she copies is from the Wikipedia entry for “floor:” “Floors may be stone, wood, bamboo, metal or any other material that can support the expected load.”

Responding to her prompt, I take ten pictures of my floor at home. Positioning my body in relation to a floor that can support the (un)expected load. I take the first step toward her work, towards supporting the unspeakable. Towards recovery. Towards being with it/her.

“A photograph shows something in relation to its position or lack of position in a world I find myself on the floor for many occasions I slide around looking for all the things I've misplaced hoping the floor will reveal them. It usually doesn't.” (-Roni Aviv)

Contained

Horodi’s interference with common art writing is revealed in an article entitled, “Why did I invent Shaul Setter.” At the time this text was published, the scholar and theoretician Shaul Setter (a real person), was the art critic of Ha'aretz newspaper in Israel. In this text, Horodi proclaims to have fabricated Setter's character, mocking his writing style by proposing how he allegedly writes:

“I stand in front of the bookshelves, close my eyes, turn around twice, reach forward, and pull out the first book that comes up in the palm of my hand. I open a random page. If given the right selection of books, any theory can fit any work of art.” (-Shai Lee Horodi, translated from Why did I Invent Shaul Setter? In Tohu Magazine, October 19, 2017)

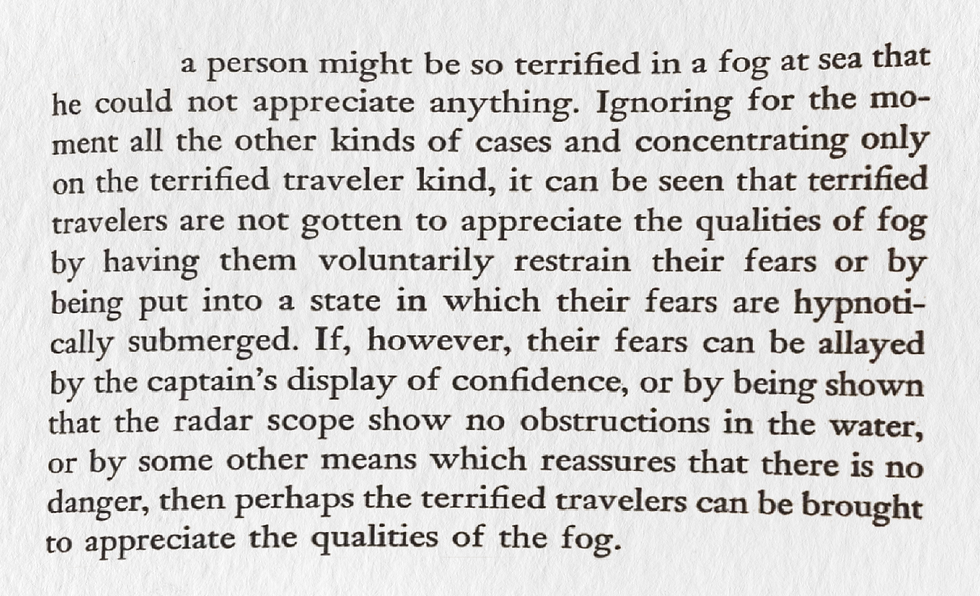

Following these instructions at home, standing in front of my own bookshelves, I pulled out Phaidon’s “The Art Box,” which is a collection of greeting cards. Obviously, not all the books on my shelves are “right” for this activity. I tried again, and this time reached for a book on the smaller shelf of art theory books. This time, it magically worked above—or perhaps in contrast—with my expectations.

Read for yourself:

(George Dickie in Art and Aesthetics: An Institutional Analysis)

You might accidentally bump into things

Should we try, first, to dispel the fog- as curators love so much to do?

The Black Square is a painting by the Russian painter Kazimir Malevich. He painted the first of several versions in 1915. A black square, however, appeared earlier in the artist’s stage design for the opera Victory over the Sun, by Aleksei Kruchonykh, Mikhail Matyushin, and Velimir Khlebnikov. The opera tells the story of a group of characters that attempt to destroy reason by disrupting time and capturing the sun. Malevich saw this work as the first painting of Suprematism—his coinage for a style that abandoned representation in favor of shapes and colors.

This exhibition tells a story about adventures with art, and begins in the darkness as we capture the sun. Are we looking for something that can only be unlearned in the absence of light?

What’s painted here?

Horodi: When I want to take a break without interrupting my concentration, I juggle. If you are ambitious, try learning to juggle three balls. If you are less ambitious, then you can practice throwing a ball behind your back with your right hand and catching it from the front of your body with your left hand, and vice versa, until you do it steadily, without too much effort.

The camera zooms into the Black Square, and we are lost in complete darkness. A few seconds later, the artist’s voice emerges: “do you know what this is?” We are no longer alone with the artwork. Horodi offers us comforting coordinates, yet does not disclose a historical context for the painting. She does not dispel the fog, nor does she provide reassurance that there is no danger. And still, a horizon is alluded to.

Maybe the painter who painted this painting painted how it feels not to understand.

Horodi created this work as part of her job at “Net.Haver” (net.friend), a social internet platform for adults with “intellectual disabilities.” It is part of a series of videos mediating canonical artworks. Horodi speaks about this work, “The world of people with intellectual disabilities is artificially limited by their environment, often stemming from a belief that they should be protected from certain thoughts… In working with people with intellectual disabilities, and talking to them about the same issues that they were prevented from discussing elsewhere, we get to fight alienation with them, theirs, and ours.” (-Shai Lee Horodi translated from Dvarim Baolam podcast, as all her other quotes in this section)

But Horodi’s Mediating Videos have circulated in other platforms beyond Net.Haver. Alienation is in every corner. Listening to Horodi, I feel invited to linger in the shadows with her and Malevich. Perhaps this is an invitation that I can only follow when I trick myself, or am tricked by the artist, to believe that I am not the target of this work.

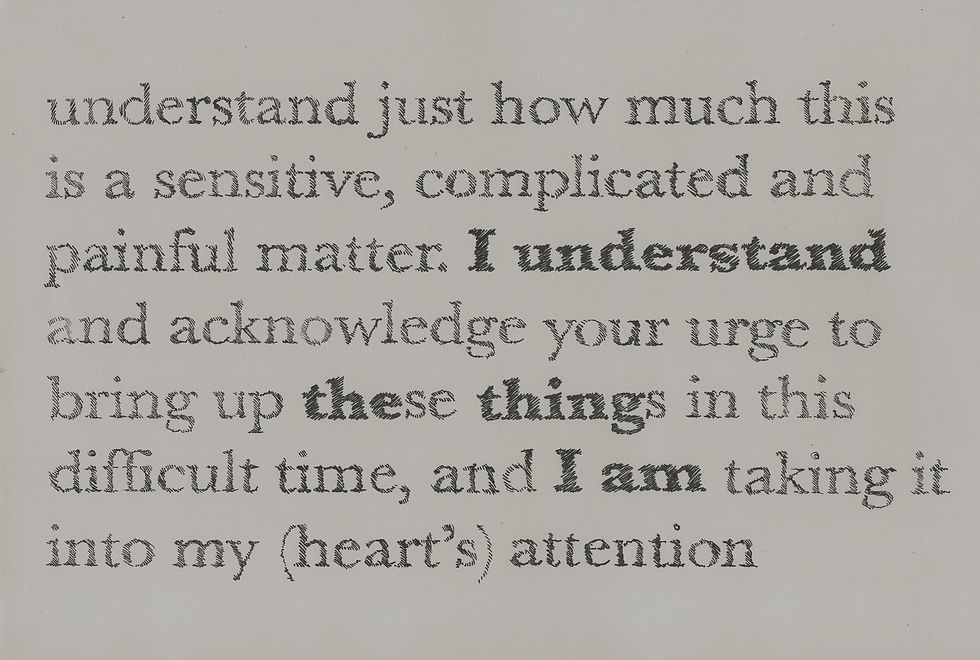

I join Malevich’s fight against reason to find empathy for our lack of understanding. Is mediation the gateway that allows every person to enter the realms of contemporary art? Or is it precisely what creates a distance, telling them they can only experience art through the mediator’s words? And who is being referred to in the word them? The French philosopher, Jacques Rancière, taught me that “to explain something to someone is, first of all, to show him he cannot understand it by himself.” (-Jacques Rancière in The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation)

Horodi is not surprised by art that engages in the segregation of people. After all, in her own words, “It is impossible to produce art that does not express social relations. And if the social relations in our society are ones of exploitation—as they indeed are —then artists will express it in their works.” In this work, I identify a fracture between explanation and exploitation. It brings to light the pain of distinction and the frustration of not understanding. According to Horodi, “It enhances a painful moment where a viewer sees something taken from him.” Or her.

I only made two balloon juggling balls, yet I managed to keep dropping them on the floor. Juggling is a recurring motif in Horodi’s practice. In 2020, she created the work Three Balls in Two, in which her hands perform the actions required to juggle with three balls, but the third ball is missing. “Juggling is done when there are more balls than hands, so you need an invisible ball to create movement,” Horodi tells the artist Yonatan Zofy in an interview for the blog Marbe Einaim. “I thought of it in the context of The 20th Seminar by Lacan, in which he talks about how male and female ‘jouissance’ is fundamentally different. For the man, it is a pleasure of the phallus; he can delight in the ‘everything’ and be able to point to it as well. While for the woman, ‘nothing is everything,’ and is her pleasure, to be able to say that it is not everything. ‘You did not point to everything,’ ‘you could not fathom all pleasure.’ Juggling is the answer to the woman who said it. It represents a masculine way of thought - finding a solution, owning the omnipotence of potency. There are two balls, and then the woman says ‘no, that's not all,’ then the man says ‘oh! Is there another ball? No problem! 'And the juggling movement begins. But it is clear that what the woman is trying to say is not that there is another ball; but that there is something else that cannot be named.”

(Shai Lee Horodi, translated from Marbe Einaim)

I have heard that Moshe Halbertal, a professor of Jewish thought, said that a good Talmudic Sugia (issue) is one that succeeds in holding as many balls in the air as possible. The polemic culture of the Talmud, one of the central texts of Rabbinic Judaism, inspired the layout of this exhibition. The original polysemic text (here, the artwork) is surrounded by different responses and interpretations in various languages, traditions, and perspectives.

Juggling among points of view, there is always something that refuses to be written. I did not point to everything.

It hurts to not understand how to explain what we mean to say

“One of the problems I have with the art field is that it is terribly clear to people how to approach art, for artists, viewers, and curators. Once a system allows us such immediate access and instruction, nothing can truly be art. A pretty vulgar manifestation of this is that curatorial texts always look the same. It’s a shame! How do you stand across from an artwork and just start writing? There's a crazy leap going on there. Curators approach writing as something awfully simple, and it's not… The question does not arise: how do you even touch art with words?”

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

(Shai Lee Horodi translated from Marbe Einaim)

The starting point for this exhibition is the provocative invitation to stand in front of an artwork and pause before immediately filling the space with mediating words. I adopt the mediating phrases from artist Shai Lee Horodi's work, Mediated Videos: Malevich, and use them as illuminating signposts to this experimental endeavor to “touch art with words.”

Get hurt or knock something over and break it

Do you know what this is?

RONI AVIV

VANESSA SANDOVAL

VANESSA SANDOVAL

ASUKA GOTO

ASUKA GOTO

Shai Lee Horodi, Mediated Videos: Malevich, 2020, video, 3:24 min

OFRI CNAANI

OFRI CNAANI

lost in translation comprises 278 pages taken from the novel "Elizabeth”, written in Japanese by Asuka Goto’s father. Over the course of three years, Goto, who is not fluent in Japanese, translated the original text to English.

When I shared with Goto the difficulties I experience understanding and mediating art, she shared with me that it reminds her of her father. Although both Goto and her father live creative lives, Goto could never read the books written by her father because she only possesses a first-grade reading level in Japanese. Her father, on the other hand, finds Goto’s work too conceptual and hard to understand. The process of translating the book, for Goto, was like building a bridge between them. Entering his language, his words, his thoughts, his metaphors. To get into someone else's language, you have to constantly move around and look for entry points. You must spend some time with it. Doors do not always open easily.

What is painted here

Hiragana

Looking for such an entry point myself, I read articles about the Japanese writing system. I am fascinated by the Kanji characters, which often maintain a formal affinity to the object or concept they depict. One Kanji usually has multiple meanings that are pronounced differently to distinguish which meaning you wish to use. 分 means to understand. Composed of the radical 刀, meaning a knife, it also means to divide into two (and also a segment; probably; maybe; minute).

I long for such a form of writing that holds within it a multiplicity of images and networks before reducing them to a knife. But one must be cautious in imposing a different way of thinking on a language, a nation, or an artwork. To create a true encounter, you have to explore, learn, imagine, and search for the other within you.

Perhaps sometimes we only build a one-way bridge of understanding. Goto’s father couldn’t understand why she created this work and called it her own. This brings up the question, who has the right to make the final decision on meaning?

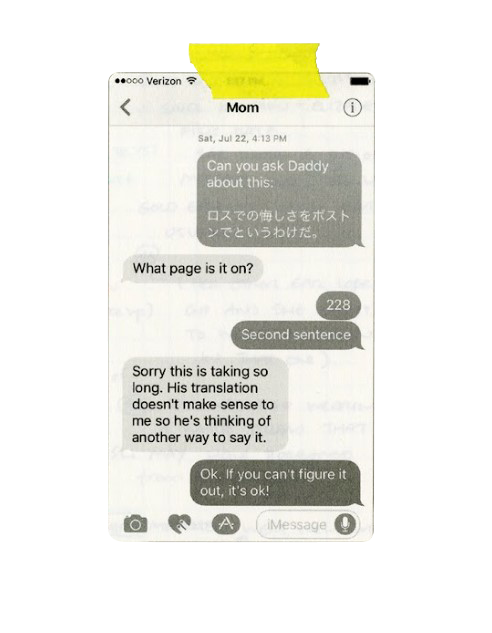

When the process of translating felt impossible to solve on her own, Goto asked her father to help.

“Because he has trouble with even the most basic technology, I would text my questions to my mom, who would physically hand her phone to my dad, who’d glance at the screen before offering a rough translation aloud in broken English. What does ガラーン mean? I texted.

He needs the whole sentence, she replied.

I switched to the Japanese keyboard on my phone and with some effort, drew the kanji onto the little screen with my index finger.

It’s quiet - nothing happening in the police station, she texted back.

Deserted? I asked, offering a more atmospheric descriptor for the scene I imagined unfolding.

No. Just quiet, she replied a few beats later.

Deserted, I wrote down, more confident in my grasp of the narrative than in my father’s English vocabulary.”

These correspondences become a sort of footnote with screen-prints of iMessages taped to the drawings. Goto is currently working on an artist book that juxtaposes her translations with a reflexive essay on the working process.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

片仮名、カタカナ

Do you know what it is?

Without light, it is very difficult to see

Get hit or drop something and break it

A paragraph in modern Japanese is usually composed of a combination of three distinct writing systems: Hiragana (平仮名, ひらがな), which is a phonetic lettering system; Katakana (片仮名、カタカナ), which is used for the transcription of foreign words; and Kanji (漢字), which is a logographic system borrowed from Chinese. I offer these three systems as titles for a few modes of experiencing and translating the work, lost in translation, by Asuka Goto.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

“My father is someone I’ll never fully know.” Goto writes, but she shows us that it is conceivable to understand a book with effort and attention, even when being illiterate in that language. It reminds me of the parable of the ignorant schoolmaster, Joseph Jacotot, as narrated by French philosopher Jacques Rancière. Jacotot was a French teacher in the 18th-century who was exiled to Belgium and had to teach French literature to Flemish-speaking students without speaking their language. Approaching this task, Jacotot gave the students a bilingual edition of the book Les Aventures de Télémaque, fils d’Ulysse (1699) and asked them to learn the French text using the Flemish translation. They read the book until they could recite it and then wrote an essay explaining the text in French. Their performance in French—a language that was never formally taught to them—was as good as French-speaking students, leading Jacotot to question the role of the master as a knowledge transmitter that brings the student, gradually, to his level of expertise. For Rancière, the book kept the two minds, the master’s and the student’s, at an equal distance. Art also bears this potentiality—keeping the artist, the curator and viewer at an equal distance.

Katakana

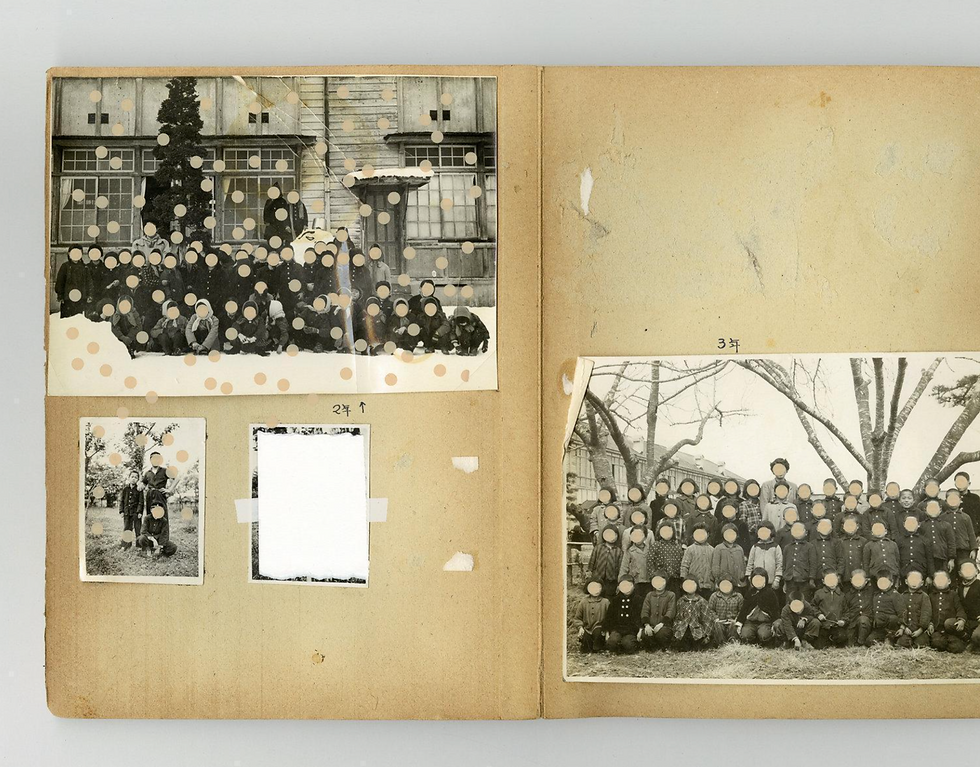

Longing to find a path to understand her father more deeply, Goto browsed through a photo album that he brought with him when he immigrated to the US, hoping to see information about his life and identity in Japan that he has not communicated verbally. In a series of silk prints, titled Photo Album, that Goto created around the same time that she worked on lost in translation, she–quite literally–pointed out holes in the story.

Photo Album 02-01, 2019, silkscreen and collage on pigment print, 16x20.

漢字 (Kanji)

My word was Davka (דווקא). Doing something Davka means willfully and deliberately taking action to antagonize. It can also mean this way, and not otherwise, or specifically of all things… It usually comes with a certain attitude, tone, and facial expression.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

דווקא

Goto: Think of a word in your mother tongue that you love or use often, for which there is no direct English equivalent, a word that takes a large number of words to explain.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

I try to copy excerpts from the artist's handwritten notes in English, but couldn't reconstruct a glimpse into the story of Elizabeth. Goto doesn’t form a cohesive text that can be read from beginning to end. If she was only interested in the English script of the book, she could have hired a translator, she told me. “It is about the struggle to understand something foreign.” The artist’s marks, notes, and fragmentary translated sentences are scattered around a photograph of each page in the original book. It resonates with the exhibition layout, and with its struggle.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

Elizabeth

Asuka Goto, lost in translation, 2015-2017

_gif.gif)

_edited.jpg)

Masechet Peah in the Mishna also describes a few unquantifiable things:

”These are the things that have no definite quantity: The corners [of the field]. First-fruits; [The offerings brought] on appearing [at the Temple on the three pilgrimage festivals]. The performance of righteous deeds; And the study of the torah.”

I am looking at the unquantified phenomena around Cnaani’s palms. Are they actually non-measurable? How do I approach them? I touch the hands on the screen and trace the circular lines with my finger from the mental exhaustion to the same issue of anxiety. The distance between my eyes and Cnaani’s work on my computer screen is three wide-open palms. The distance between Cnaani’s palms and words is the distance between my words and palms. The distance between the projected image of Cnaani’s work in my primary visual cortex and my eyes who watch it is the visual nerve. The distance between my fingers moving on the keyboard and (un)quantified self is less than four fingers. The distance between the words I am writing on a word file titled “Ofri Cnaani draft” and the pdf “MLF_portfolio_2021” and within it her work, is 24 open windows on my computer.

The distance between myself working at my desk and the sunny day outside is unquantifiable. The distance between the moment I first looked at “(un)quantified self” this morning and felt the sensation when not even one interesting thought comes to mind, and the 1166 characters counted in this file, might be the measure of lack of self-awareness.

What is painted here

The skin that can see

I borrowed this measurement method from Measures of Closeness: A Lexicon of Gestures - a performative practice that Cnaani developed with Stella Geppert and Evan Siebens while in quarantine during the first days of the COVID-19 pandemic. During a virtual workshop, the artist invited participants to use their bodies as measuring apparatuses. Through individual and collective movements, participants were invited to perform the newly created relationships between the different bodies, as well as between body and space.“In search of closeness, we give up the image of the whole and remain with the visual aspect of only a few organs.”

Twenty-four hands of twelve bodies are dancing to measure the distance between the touching hands and the screen. Twenty-four arms are sent to the edges of the camera to greet the body in the zoom square next to them. Where is your body?

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

The murmur of electrons when a living skin touches the plasma screen

Do you know what it is?

Without light, it is very difficult to see

Get hit or drop something and break it

(un)Quantified Self is part of a series of large-scale digital prints titled, You Are My Statistical Body. In this body of work, Cnaani photographs her hands and digitally annotates them, juxtaposing ancient and contemporary forms of knowledge. In (un)Quantified Self, Cnaani uses self-quantifying infographics to point to non-measurable phenomena. I use these unquantified phenomena written around the wrists and arms in Ofri Cnaani’s work as titles to its mediation.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

The distance between the elbow and the tip of the hands has been used as a unit of length in ancient cultures: “It is to be square, a cubit long and a cubit wide, and two cubits high.” (Exodus 30, 2) Our bodies have been used as our first unit of measurement in the world. Our intuition for distance and dimensions is rooted in our embodied existence. “A particular human scale is inherent to the intelligibility of Earth around us.” (-Timothy Clark in Ecocriticism on the Edge) It is more difficult for us to comprehend things that are larger than what our bodies can handle, things in the world to which we cannot attribute a corresponding parallel in our flesh.

The Flesh

Some people constantly and compulsively quantify their bodies. “If we want to act more effectively in the world, we have to get to know ourselves better,” declared the quantifying master Gary Wolf in a TED talk . If the “Quantifying Selves” exceed what their actual body can perceive, they use technological devices, often sensors that are worn on their wrist, to collect and analyze numerical data on daily life performance such as caloric intake, sleeping quality, and physical activity. Perhaps they believe that everything can be measured. Controlled.

The cruel optimism of applying

Ofri:

I would be happy if you could write down a list of 10 questions.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

I play with the questions to summon meeting points among the works in the exhibition. And this is how my exploration into being with art ends.

1. How do you reach out your hands?

2. How do I find these words in my arms?

3. How do I find these arms in your words?

4. Why are there holes in everything?

5. How do you make the hole bigger and move within it?

6. Is this a translation machine? Could it translate what has been “lost in translation” in Asuka Goto’s work?

7. Could this “mouth smell” meet with Vanessa Sandoval’s mouth and yours on the screen?

8. Could Ofri Cnaani’s palms “support the unexpected load” (in Roni Aviv words) of everything that is impossible to understand?

9. How would Shai Lee Horodi mediate the “unquantified”?

10. What is the distance between you and all of this? Could you embody it with your eyes? With your hand moving the cursor on the screen? Could you be-with-us?

The pathetic hope that someone will understand you without words

But who is “they” that we are talking about? Thinking of Cnaani’s work, I kept differentiating between myself and those quantifying selves. Only now when I finish writing, it dawned on me. Every morning I use a thermometer to check my basal body temperature. I am constantly looking for precursor signs of disaster in my body. Cnaani’s work reminds me that the residue that cannot be quantified is a key to slipping away from my need for control. In her words, it points to “the potential leakage of information, the hole in the archivable, and the noise in the computable. The imperfect edges represent spaces of reduced governmentality. As for all our concerns, there is always something that drops out.” I hope there is. Life happens in the holes. Even the body cannot encompass an artwork in its entirety. I cannot quantify or approximate all the distances, words, organs, and spaces between you, myself, and the artworks. I don’t want to seek order in the chaos of the experience of being with art. What I can do is reach a hand with little brains inside the fingers that weave stories with links and write in semi-circles.

The moment I don’t even know

Ofri Cnaani, (un)Quantified Self, digital print, 100x150 cm, 2021

Dr Ofri Cnaani is an artist and researcher. She works across time-based media, performances, and installations. She is a guest professor at TU Wien and a research fellow at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA) at the University of Amsterdam. Her work appeared at Tate Britain, UK; Venice Architecture Biennale; Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC; Inhotim Institute, Brazil; PS1/MoMA, NYC; BMW Guggenheim Lab, NYC; Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna. Cnaani currently works on a project at the International Space Station (ISS).

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

OFRI

CNAANI

Do you know what it is?

Without light, it is very difficult to see

Get hit or drop something and break it

Vanessa Sandoval is a visual artist with a practice in the fields of sculpture, drawing, and installation. In 2014, she was a recipient of the BLOC grant, in Cali. In 2016, she obtained a national internship in visual arts from the Ministry of Culture and participated in the 44th National Artists Salon. In 2017, she was a resident of RÉSO in Biella, Italy, and was awarded with the V Sara Modiano Prize, in Bogotá. In 2018, she was invited to show her work at Nuevos Nombres, Banco de la República, Bogotá. Lives and works in Cali, where she was the coordinator of the Documentary Center at Lugar a Dudas until 2019. In that year she was invited to participate with an intervention in the exhibition Voces para Transformar Colombia by the National Museum of Memory. Currently doing a residency in Center for Book Arts in New York.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

VENESA SANDOVAL

Roni Aviv (born 1992) is a visual artist, based in New York. Aviv works with photography, text, and installation to give form to a psychological space of re-processing experiences. Aviv holds an MFA in Visual Arts from Columbia University. Her work has been published and exhibited internationally. Recent exhibitions include the Center for Book Arts, Real Art Ways, Longwood Art Gallery, Steve Turner Gallery, and The Jewish Museum. Aviv has recently been published in BOMB, GRANTA, and Erev Rav magazines. Recent residencies and fellowships include NARS (2021), Center for Book Arts (2022), and AIM Bronx Museum fellowship (2023).

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

RONI

AVIV

Asuka Goto is a New York-based visual artist whose recent work explores the complex, cross-cultural relationship she shares with her Japanese father. Goto received an MFA in Sculpture from Tyler School of Art and a BA and Post-Baccalaureate Certificate from Brandeis University. She has participated in residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Joan Mitchell Center, and Djerassi Resident Artists Program, among others. Goto has received the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, NYFA Artists Fellowship, Jerome Foundation Travel & Study Grant, and Joan Mitchell MFA Grant. “lost in translation”, her 2018 solo show at Tiger Strikes Asteroid NY, was named one of the “Top 15 Brooklyn Art Shows” of the year by Hyperallergic.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

ASUKA

GOTO

Maya Bamberger (born 1991, Jerusalem) is an independent curator based in Tel Aviv.

In her practice she explores the boundaries of knowledge production and how the imaginary can intervene in writing about art to offer new encounters between the artwork and the viewer.

Previously the curator of RawArt Gallery in Tel Aviv, a gallery dedicated to representing emerging and experimental artists, Bamberger has curated several solo exhibitions, including Noam Toran’s We Crave Blood (2023), Ester Schneider’s Temperance (2023), Keren Gueller’s Wet Collection (2022), Dov Heller’s Nirim (2021), Sharon Glazberg’s Nowhere (2021), and Sagie Azoulay’s Ernie (2020). One of her primary initiatives at the gallery was the Shuttle project, which promoted artists at the beginning of their careers. She also curated group exhibitions and led projects and collaborations.

As an independent curator, she co-curated with Ronny Koren, accompanied by Sergio Edelzstein, an exhibition of artist Hilla Toony Navok at the On Curating Project Space in Zurich for the multi-format series Choreographing the Public.

Bamberger holds a MAS in curatorial studies from Professor Dorothee Richter’s program at Zurich University of the Arts and a B.A. in art history and cognitive science from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She is a fellow in the Alma program for the years 2021-2023, writes for OnCurating magazine, and is one of the founders and editors of Shoket magazine for curating of the Israeli Association of Curators.

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

MAYA

BAMBERGER

Shai Lee Horodi (b.1993) is an artist, writer and educator based in Tel-Aviv. She showed solo exhibitions at the Tel-Aviv Museum of Art (2015) and at Dvir Gallery Tel Aviv (2019, 2020) and published texts at Tohu Magazine (2017, 2018), Erev-Rav (2021) and Tyota Magazine (2021). Horodi teaches at Minshar School of Art and works with people with cognitive disabilities. She created a video guide for the Tel-Aviv Museum of art’s permanent exhibition of the collection (2022) aimed at people with cognitive disabilities. Horodi studied at The Midrasha Faculty of the Arts, Beit Berl (2013-2015) and received her MFA from Northwestern Department of Art Theory and Practice (2019).

It hurts not to understand how to explain what we want to say

SHAI LEE

HORDI